I have been a teacher for 27 years, a Headteacher for 12 years and, at the age of 51, this much I know about coping with the university drop-off. We’ve just got back from dropping Joe off at university. At 6 am I got up to write something because I had to write something. This is it...

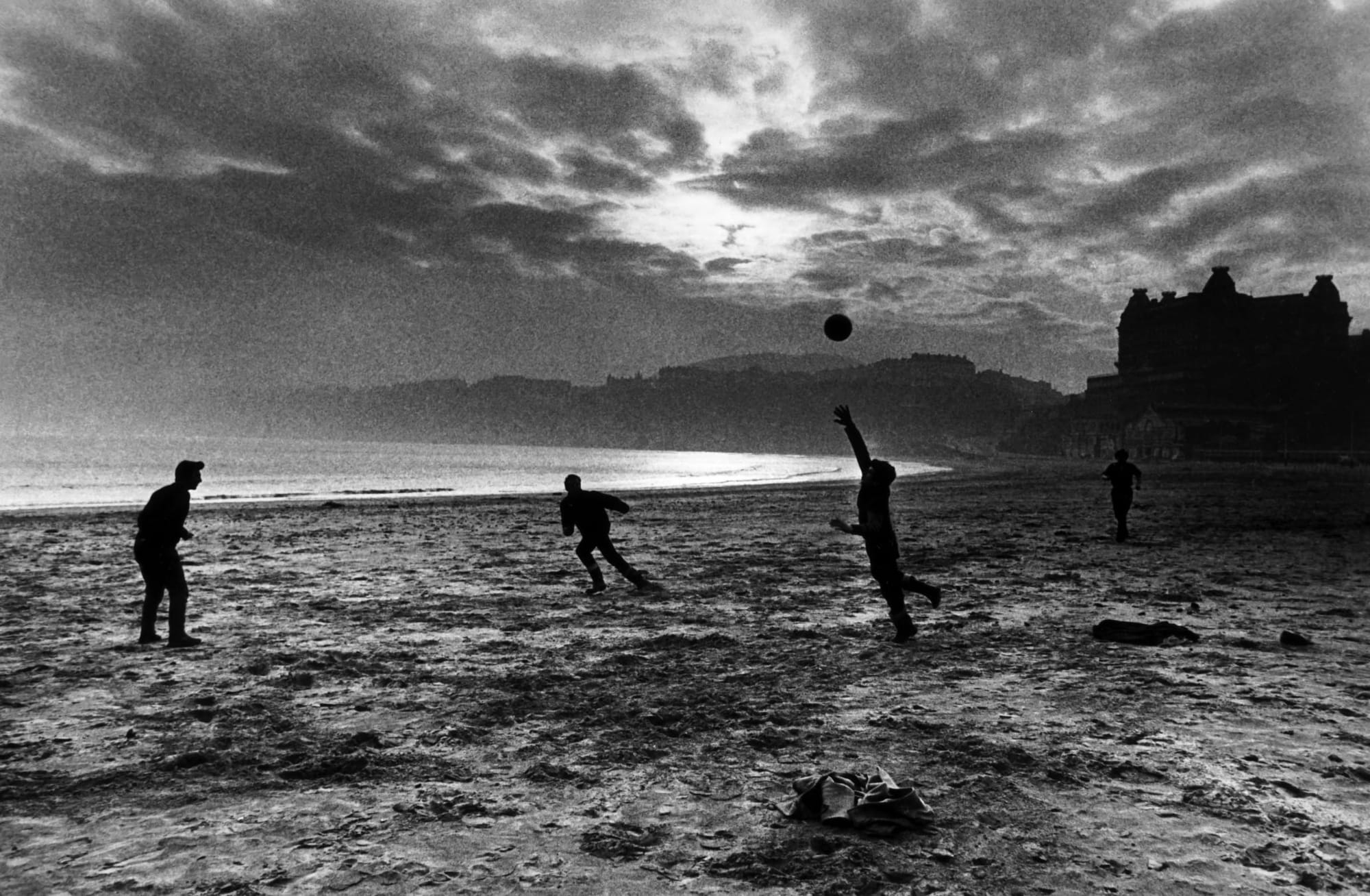

Fishermen playing during their lunch break, Scarborough, Yorkshire, Great Britain, 1967, © Don McCullin

Men have played headers and volleys ever since football began. H&Vs, as it is commonly known, omits the more mundane elements of the game like tackling and throw-ins. Instead participants revel in the glamour of the improbable shot and the flamboyant finger-tipped save. In headers and volleys we can all, for an ecstatic moment, shape shots like Ronaldo or leap like Buffon. And it is the temporal nature of the ecstatic moment which Don McCullin captures in the image, Fishermen playing during their lunch break, Scarborough, Yorkshire, Great Britain, 1967.

McCullin is most famous for his work in Vietnam and other conflict zones, but he identifies this picture as his personal favourite. It was taken during a photographic odyssey along the East coast of England. Cartier-Bresson defined his concept of the decisive moment as, The simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression. I think McCullin’s Fishermen playing during their lunch break exemplifies that definition as well as any photograph I know. I confess I never tire of looking at this image. What is fascinating about the shot is its precise organization of forms. When you play headers and volleys you always need someone way out on the wing to cross the ball into the goalmouth. Someone has to volunteer to be the goalkeeper. Everyone else mingles around waiting for the opportunity to crash their boot laces through the ball and score an unimaginably brilliant goal. All the participants of a great session of headers and volleys are present in their correct place. The lad on the far right crosses the ball. The goalie makes an outstretched effort to palm the ball away. The two others anticipate which way the ball is going to fall. A second later and the man on the left might well be thumping the ball into the imaginary net or, perhaps, knocking it into the centre for his mate to score.

What elevates this image beyond the prosaic, however, lies in its combination of revelatory detail and its sense of solitary grandeur. Let’s begin with the detail. The figure on the left has a perfect rock and roll quiff haircut, anchoring him securely in the mid-1960s. The goal posts are of the traditional throw-two-jumpers-down variety, except that the left-hand post in the foreground seems to be a specialist sea fisherman’s garment, maybe a fish-filleting apron. Disturbances in the claggy sand form a record of the headers and volleys game. Each participant’s movement is traced in the sand’s topography. The keeper’s activities are particularly well-defined and, according to the sand, there has clearly been a close confrontation between him and the rockabilly after a deep cross to the far post.

Whilst the detail is fascinating, what elevates this image is its setting. To begin, the four men are alone. The image would lose all its power if just one more observer, other than McCullin, were present. The beach sweeps round to the bay’s edge and I cannot look at the poem without recalling the last line of Ozymandias, The lone and level sands stretch far away. Shelley’s poem is, perhaps, the most powerful condemnation of those of us who get beyond ourselves. Anyone on that beach who thought he was Geoff Hurst or Gordon Banks – it was, remember, England in 1967 – is grounded by the photograph’s impassive background. The Scarborough Hotel sits above the beach watching imperiously. Beyond that the winter sun looks on through the breaks in the thin cloud. The sky is Turneresque, The Fighting Temeraire in greyscale. The stillness is palpable. The figures are silhouetted against this unsmiling backcloth.

And then there is the football itself. In Camera Lucida Roland Barthes identified the twin concepts of studium and punctum: studium denoting the cultural, linguistic, and political interpretation of a photograph; punctum denoting the personally touching detail which establishes a direct relationship between the observer and the object or person within the photograph. In this photograph the football is my punctum. The football is both a detail of the image and part of its detached remoteness. It sits caught forever just out of the goalie’s reach. It is also planet-like, hovering distantly over the trivial game and the fisherman’s forthcoming afternoon travails in the North Sea. It is perfectly sited just above the far trees, of the sky rather than of the earth. Of all the forms in this photograph, it is, to use Cartier-Bresson’s own words, the one most precisely organised.

One May half-term, many years ago, I played football on a sunlit Gibraltan beach with Joe. It was breezy, the ball was too light but his small feet zipped across the beach effortlessly. At the end he fell down front-first in the sand and I captured his indefatigable spirit in this portrait.

It was a moment in time, as was the game of headers and volleys in McCullin’s photograph. The transitory nature of things makes them essentially beautiful. As JL Carr wrote, It is now or never; we must snatch at happiness as it flies.