Earlier this year I catalogued the many insights gleaned from educational experts which have been most influential in my curriculum thinking, in a post entitled, This much I know about… the principles of curriculum planning in action. In a series of short essays I am exemplifying in more detail ten of those influential insights, and explaining why I think they are so important to progressing pupils’ learning. This post explores Dr Anita Devi's suggestion that a learning model can help you plan and teach adaptively.

I trained to teach in 1987-88 at the University of Sussex. Not once during our PGCE course did we consider how pupils learn.

It was at Huntington School in York, some 25 years later, that Alex Quigley began pushing me to think harder about how we taught and how pupils learnt. It was meeting Jonathan Sharples in 2012, when he was working at the University of York's The Institute for Effective Education, that helped me understand further how I might begin to shape my teaching in a way that was most likely to result in my students learning what I had taught them. Before then – for a quarter of a century – I had developed my teaching practice by trial and error.

Until I met Jonathan (and, subsequently, Tom Sherrington, Rob Coe, Stuart Kime, Becky Allen, Becky Francis, Tom Bennett, Daisy Christodoulou, Mary Myatt and a host of other deep thinkers about education) my students had always done pretty well in their examinations. But once I started working hard on improving my teaching in an evidence-informed, deliberate way, my students began to make greater progress against every possible metric.

The book that changed me as a teacher was Nuthall's Hidden Lives of Learners. I will leave Tom Sherrington and Alex Quigley to go into the detail of Nuthall's research; what I did was to make sure that I taught each element of my A Level Economics content in three different contexts. It worked an absolute treat!

After Nuthall, I read Willingham's Why Don't Students Like School. It made me think about getting my students to think hard. All the time. In every lesson.

Post-Willingham, my next influence was “Cognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking Visible” by Collins et al. It was so influential to my teaching and, indeed, the teaching at Huntington, that several years later I edited a book about how to implement, across the curriculum, the approach that particular research paper advocated.

Buoyed by the efficacy of so much of what we were reading and learning, Alex and I were at the vanguard of developing the Research School Network, which, along with the researchED movement, has been a game-changer in helping the profession develop evidence-informed practice in our schools.

Then Tom Sherrington sent me a Word document to read, about a paper on how to teach by a bloke called Rosenshine. Tom wondered whether it was worth publishing. I said I thought it was, and the rest, as they say, is history. Tom and Oliver Caviglioli then published the first of their Walkthrus series, which detailed their learning model, based upon Willingham's cognitive science research findings.

The final pieces of the jigsaw, which have helped form a clear view of how we might shape our teaching in a way that will most likely optimise pupils' learning, have come from the work of people like Sarah Cottinghatt, Greg Ashman and Barbara Oakley.

What Willingham, Rosenshine, Oakley et al. profess is all conditional. It is what the evidence suggests, currently, about how our brains work when we learn something. Fundamentally, learning is a permanent change to our long-term memories. But nothing is definitive. All I would say is that it all makes sense and when I have translated the theory into classroom practice, I have seen my students make better progress in their learning.

It is easy, of course, to parody teaching and learning that is based on evidence from cognitive science as some robotic process. But imagine an awe and wonder teacher – one like those I championed in an earlier post in this series – passionate about their subject, utterly enthused in the classroom, who was able to combine the awe and wonder stuff with evidence-informed pedagogy which is deliberate and thought through in detail. What a teacher that would be! Indeed, there are now many such teachers across the country, who have combined their teaching experience with what research evidence says has the best chance of helping pupils learn. There is always a third way; the binary nature of so much educational debate is unnecessary.

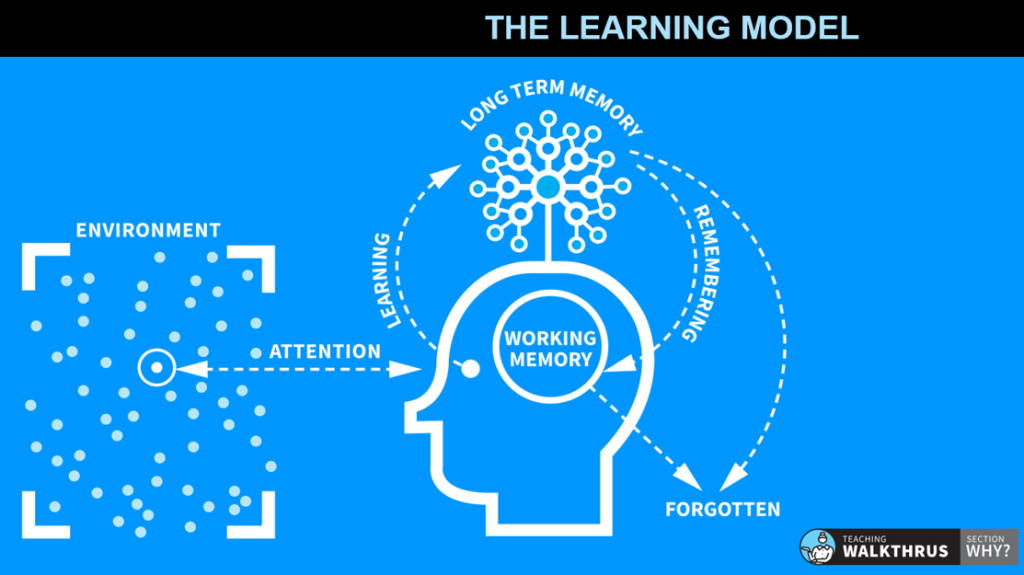

All of which brings me back to the question, "Why do we need a model for learning?" When Mary Myatt and I interviewed Dr Anita Devi for SEND Huh, she made an illuminating comment: "You need a model of learning. It gives you the questions to ask when a child is not learning." It made so much sense. If a student is finding something hard to learn, where in your learning model is the problem? Do they have insufficient prior knowledge about the topic to make sense of what you are presenting to them? Is what you are presenting to them unable to gain their 100% attention? Are there distractions in the class? Are they finding it hard to hold 3 or 4 things in their working memory? Are the learning tasks you are setting not challenging enough to make them think? Did they miss one of the times you went back over the topic?

With a learning model, you can interrogate your teaching and the conditions for learning in your classroom to see what you might adapt to help students learn more effectively. Without a learning model, you are teaching by trial and error, just like I did, year, after year, after year.

An important aside: once I became deeply engaged in understanding how learning happens, the overall outcomes at Huntington improved too. As Viviane Robinson's research suggests, the best thing a headteacher can do to help improve student outcomes is to "promote and participate in teacher learning and development."

Next week, on 14 December, Mary Myatt, Tom Sherrington and I will be in London, talking about what we have learnt over the years about the curriculum. The event is called: Curriculum Masterclasses: A Christmas Celebration! It is only £30 (to cover costs) and John Catt Education have thrown in a free book of your choice from the range of books the three of us have published. You can book a ticket here. Come and join us!