This is my fourth and final post on curriculum development. Here I propose a way of developing the curriculum which takes everyone with you, is user-friendly, is based upon sound principles, is academically aspirational and is focused upon developing teachers’ expertise.

It is not just Adam Boxer who doubts whether the current focus upon developing the curriculum will last: Alex Quigley is not sure; Claire Stoneman has her concerns; Professor Becky Allen & Ben White even raise the spectre of a curriculum crash. And Adam’s tweet has had 1,127 likes…

Boxer, Quigley, Stoneman, Allen & White. They are big thinkers – we ignore them at our peril!

Despite the worries, the focus on the curriculum must be sustained. Whilst OFSTED’s latest inspection framework is largely responsible for the attention being paid to the curriculum, it is remarkable, when you think about it, that we haven’t always been paying close, relentless attention to what is being taught in our schools. As I wrote in my first post in this series on curriculum development, what is a school if it is not what our students learn?

So, what is there to do if we are going to keep a productive focus upon curriculum development?

Let’s begin with the SLT. The thing is, what else should school leaders be doing but supporting subject leaders to develop the curriculum and supporting all teachers to improve teaching and learning? What else are those school leaders who aren’t do doing these two things, so busy doing that is more important (I know, I know [like, I really DO know]…setting up testing stations, writing grading policies, updating the Risk Assessments…)? To be fair, we have been walloped by the pandemic which means, according to OFSTED, that there is “more work to be done” on the curriculum in schools.

And yet, the pressures of the pandemic are easing. We can begin to refocus upon our purely educational priorities. There is a job for SLT in schools to do, and that is to get themselves securely informed about the school curriculum. If you read Mary Myatt’s book, Gallimaufry to coherence, or Symbiosis by Kat Howard and Claire Hill, or researchED’s The Curriculum edited by Clare Sealy, or The Secondary Curriculum Leader's Handbook, whose editor is Roy Blatchford, or Dylan Wiliam’s Principled Curriculum Design, you will have made huge strides in your understanding. If you want an in-depth analysis of the curriculum by subject, UCL’s What should schools teach? is superb. For an overview of everything you need to know just read Tom Sherrington's The Learning Rainforest. All of these books are accessible reads. And then you might, with appropriate levels of humility, spend some time talking to your middle leaders about the aspects of the curriculum they are leading. I guarantee your colleagues will love being asked to talk about their subjects.

SLT must have a profound knowledge of curriculum development processes, the principles of curriculum design and the breadth of vocabulary used currently. They have to know their stuff or why would knowledgeable subject leaders ever respect them?

So much for the school leaders. People enter the teaching profession for myriad reasons. Some because they want to work with children, some because they want to pursue their degree subject, some because they couldn’t think of what to do when university finished, some because they tire of the corporate world and want to do something meaningful.

With such a wide range of professional motivation amongst teachers, the variation in curriculum knowledge and understanding is similarly broad. To what extent, then, should teachers decide what is taught? Do we entrust curriculum design to those teachers who do not have a profound understanding of their subject?

Luminaries such as Christine Counsell and Clare Sealy are leading the discussions about what should and should not be taught in classrooms. There are different types of knowledge, which we value differently; the intellectual arguments are both perilous and fascinating. There are a few subject experts who are revelling in the current debates surrounding the school curriculum.

There is, however, a huge gap between people like Christine and Clare (whose work I respect without qualification) and the vast majority of England’s 495,000 teachers. Younger teachers who see teaching as a lifelong career during which they get geekily engrossed in their subject are in the tiny minority. Few teachers have the motivation to become deeply engaged in curriculum development; even fewer have the time (all of which is, as I explained in my first blog in this series, absolutely fine).

The increase in workload in developing curriculum materials at every key stage in England has been enormous. Yet, if you dictate to teachers what they teach and provide them with all the materials, you’d be surprised just how strongly many would object to such an imposition.

So, without dumbing down the intellectual nature of the exercise, what can school leaders do to support their colleagues to develop the curriculum? How can school leaders make the complex process of curriculum development an accessible and doable joy rather than a burden? Can the complexity of curriculum development be made simple without being simplistic?

Begin by announcing boldly that you are dedicating a year’s training time to upskilling everyone in curriculum design. In terms of teacher learning, ensuring that everyone understands the processes of developing the curriculum is the school’s single CPD focus, and then find every smidgen of time you can for colleagues to be trained.

Begin in September with the principles of curriculum design. Dylan Wiliam’s pamphlet is illuminated by Stephen Tierney in a short post called “Seven Principles of Good Curriculum Design”. It is gold dust. Decide collectively the purpose of education at your school, and then prioritise Wiliam’s seven principles of curriculum design. Unintimidating stuff which establishes a baseline for the rest of the curriculum development work for the year.

Then agree a common terminology that you will use to discuss the curriculum. In my second post I collected together definitions of the most commonly used terms when discussing curriculum development. These terms can be intimidating to many of the 495,000 teachers in our schools.

We shouldn’t be intimidated by some of the tremendous teachers and speakers who make us feel this language and understanding is normalised. Only a minority of existing middle leaders have the language being used commonly about curriculum theory and so it needs a steady, pragmatic approach if we are to meet middle leaders where they are.

When it comes to developing the curriculum, I would argue that the following three terms will suffice:

- Core subject specific knowledge: what you want students to know, understand and do in a specific subject e.g. Pythagoras’ Theorem;

- Subject specific strategies to use you core subject specific knowledge: How you apply Pythagoras’ Theorem to solve a mathematics problem.

- Problem solving strategies: How to think about how to solve problems when your subject specific strategies do not seem to work (often referred to as metacognitive strategies).

Collins et al. would use three slightly different terms, but essentially they mean the same things: domain knowledge; heuristics; control strategies…but heuristics is not user-friendly enough for me.

The next stage is to lay out for colleagues exactly what you want them to do with regards to the curriculum. Remind colleagues that we have been developing our curriculum for years – constantly build upon what you have already, like painting the Forth Road Bridge. Curriculum development is never done.

I don’t think curriculum review is so hard. One might argue that a subject team has largely cracked it when they have agreed:

- upon the core subject specific knowledge they want a student to have grasped by the end of Year 2/6/9/11/13 in their subject;

- how to teach the core subject specific knowledge in a way that models the subject specific strategies to use that core knowledge to problem solve;

- a well-planned assessment regime which allows teachers to know whether students have learnt what they have been taught by the end of Years 2/6/9/11/13;

- how to model wider problem solving strategies;

- to follow Michael Fordham’s principle of letting the subject matter determine the pedagogy.

Ask the following questions to subject teams as a basic starting point for reviewing any aspect of the curriculum:

- What is the core subject specific knowledge you want a student to have grasped by the end of Year 2/6/9/11/13 in your subject?

- How do you then plan to ensure that they get to that point?

- What are the subject specific elements of your pedagogy which ensure that you teach your core subject specific knowledge to avoid students’ common misconceptions?

- How do you teach the core subject specific knowledge in a way that models the subject specific strategies to use the core knowledge to problem solve?

- How do you build in assessment opportunities to ensure that you know whether your students are learning what you are teaching?

One other fundamental question is worth asking: Why do you teach that, then? Mark McCourt is particularly good when it comes to structuring a subject curriculum: “There is no point in trying to lay another brick unless the brick underneath is secure. Those bricks have to be ordered extremely carefully.” In his essay The Learning Episode, he wrote that, “curriculum is the single most important tool we have at our disposal. A carefully planned route through our subject – which is not linear, but complex and takes into account forgetting and unlearning as well as learning – is vital if we are to know when and HOW to reveal the canon of our discipline.”

Responding to these questions collectively will prove fruitful; after all, informed debate is the fuel of curriculum development.

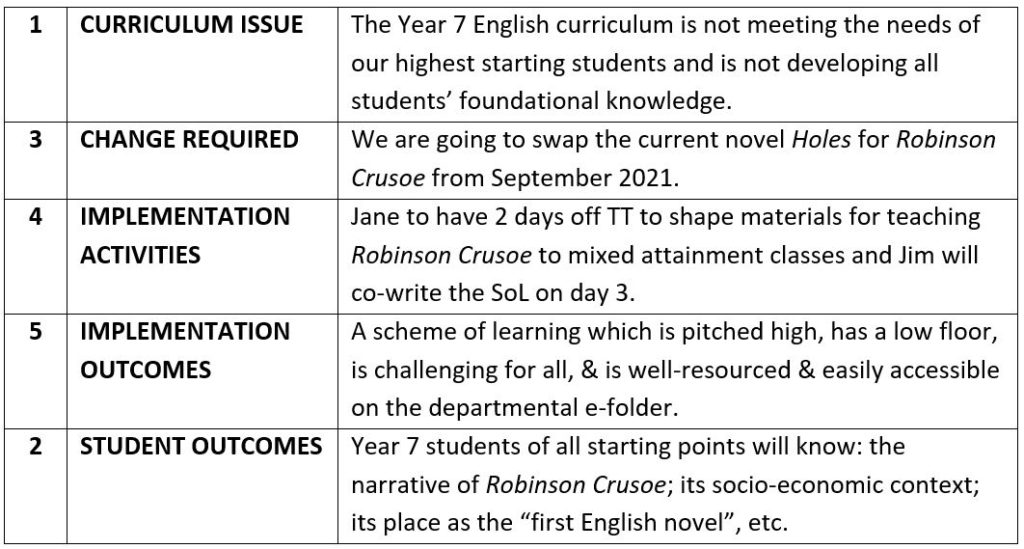

Once you have answered those questions, tackle the curriculum issues you want to resolve, one-by-one. Take the first issue; instead of immediately deciding what to do about that issue, go to the end of the process and describe the change in students’ learning you would like to see. Then go back to the problem and decide upon the change required to secure the improvement in students’ learning you have identified and outlined.

Once you are clear about the curriculum change you want to make, devise implementation activities to ensure that the change is realised successfully so that students’ learning improves. Lastly, identify the outcomes of those implementation activities. Building implementation into formulation is crucial to successful curriculum change. Sometimes those implementation activities are incredibly prosaic, as this example illustrates:

Ultimately, busy teachers are relatively happy to be provided with materials they can tweak to make their own and to have some input into what is taught. And they like to be led, so the curriculum leaders are key in developing the curriculum. But that comes with a caveat, expressed concisely by Alex Quigley, when he wrote: “If we don’t face head-on the significant challenge of teacher development, then our exciting curriculum debates and plans will come to nought”. A post by a Minnesotan teacher takes my point further. Jon Gustafson argues that three things work when it comes to supporting teachers to develop the curriculum and associated resources:

- Teachers adopt new resources that are manageable.

- Teachers are more open to resources that incrementally build on prior expertise.

- Teachers are more open to resources that directly address context-specific needs.

He finishes by pointing out that, “If a teacher is struggling with a new curricula or feeling anxious about a new resource, that should be a cue to listen more and judge less”.

School leaders committed to meaningful curriculum design would cover most, if not all, of what is needed to reshape what students learn in their schools if they followed the advisory bullet-points below, especially if they emphasised the importance of effective implementation:

- Learn about the curriculum for themselves.

- Show humility by using the language of support rather than the language of accountability when it comes to working with subject leaders on developing the curriculum.

- Agree the principles of any curriculum redesign, using Dylan Wiliam’s Principled Curriculum Design as a starting point.

- Define the general terms used to discuss curriculum design, without over-complicating things.

- Set up a Curriculum Development Group (CDG) comprised of middle leaders and led by the middle leader who has the greatest expertise and is most likely to be trusted by his or her peers to orchestrate the work.

- Remind colleagues that we have been developing our curriculum for years – constantly build upon what you have already, like painting the Forth Road Bridge.

- Give a generous time-frame for curriculum review – three years for a complete overall is reasonable.

- Provide time for expert training of middle leaders on curriculum development during CDG meetings.

- Insist that all members of SLT are trained in curriculum development and work alongside the subject leaders they line manage when they are reviewing their subjects’ curricula.

- Ensure that curriculum development work is privileged on training days and at subject meetings.

- Seek expert support if required – especially in niche subjects like Computer Science.

- Stress that the debate about the curriculum is central to curriculum development – there is no off-the-shelf quick fix to developing a challenging curriculum for your students.

- Fund membership of Subject Associations, which extend the curriculum conversation beyond the confines of your school or MAT.

- Encourage teachers to join local subject-based curriculum groups and give them time to attend meetings.

- Emphasise that the National Curriculum is the starting point upon which any individual school curriculum should be based – we are not starting from scratch.

- Encourage curriculum development which has local colour; living in York is a gift for any history teacher and I know one school which begins Year 7 with a tourist bus ride around the city for the whole year group.

- Ensure that a senior leader co-ordinates the curriculum towards vertical coherence - teach The First World War in history in the term before English teach The War Poets, not the term after...

- Stress repeatedly that any curriculum development is not about pleasing the regulator, but providing a challenging curriculum for all our students.

For too long we have implemented change in schools badly. A curriculum crash was predicted by Becky Allen and Ben White on 30 November 2019, just as SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, began infecting people in China. Maybe the pandemic has given us space to think again about how we implement curriculum change, before we career off the road and our curriculum developments crash into a wall of misunderstanding, rushed implementation and damaging frustration for everyone involved.

So, a silver lining to the gargantuan Covid-19 cloud could see us begin the new school year in September ready to realise an alternative to Adam Boxer’s rather doom-mongerish equation, one that goes something like this:

Comprehensive understanding of curriculum design at all levels + well-resourced & well-designed implementation of the new curriculum = a very good thing for our colleagues & our students