I like the notion of simplexity: making it is as simple as possible to complete a complex task. Teaching a class of 32 students on a wet, windy Thursday afternoon in November is incredibly complex; there are, however, a number of simple processes which – if implemented with care and attention to detail – can make teaching in such a situation highly effective. Kate Jones and Dylan Wiliam, for instance, have just published a brilliant article on the seemingly simple technique of “Think-Pair-Share”.

Whether those 32 students have all learnt what you intended them to learn is pretty difficult to discern. Indeed, Tom Sherrington claims that, “in a class of multiple individuals, it is not straight-forward to find out how successfully each individual person is learning, identifying what their difficulties or gaps are and then to use that information to close their learning gaps with appropriate responses.” He calls this, “The #1 problem/weakness in teaching”.

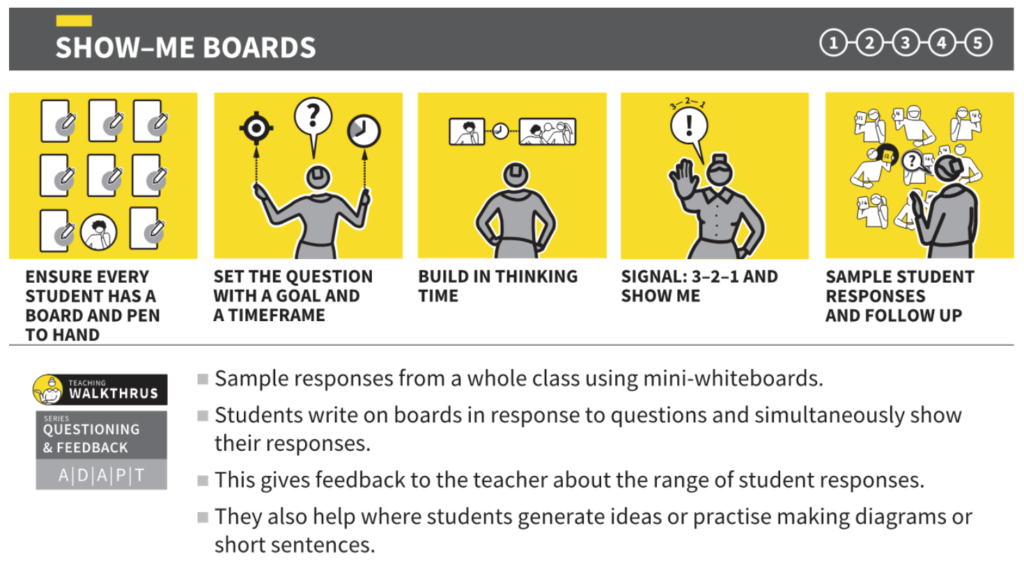

When you are checking for understanding, asking students to write down answers to your questions on mini-whiteboards can be hugely helpful. But like all seemingly routine processes, its effectiveness depends upon how it is implemented. When students are using mini-whiteboards, I have seen a number of micro-errors which, cumulatively, reduce the effectiveness of the technique and provide the teacher with imperfect feedback:

- Students write on their mini-whiteboards without attempting to hide what they are writing from their neighbours, which encourages copying of answers;

- Once they have finished writing, students do not actively hide their responses from their neighbours which results in further copying;

- Students raise their mini-whiteboards when they have finished writing their answers, rather than when asked to by the teacher;

- Students wave their mini-whiteboard around, making it hard for the teacher to see what has been written;

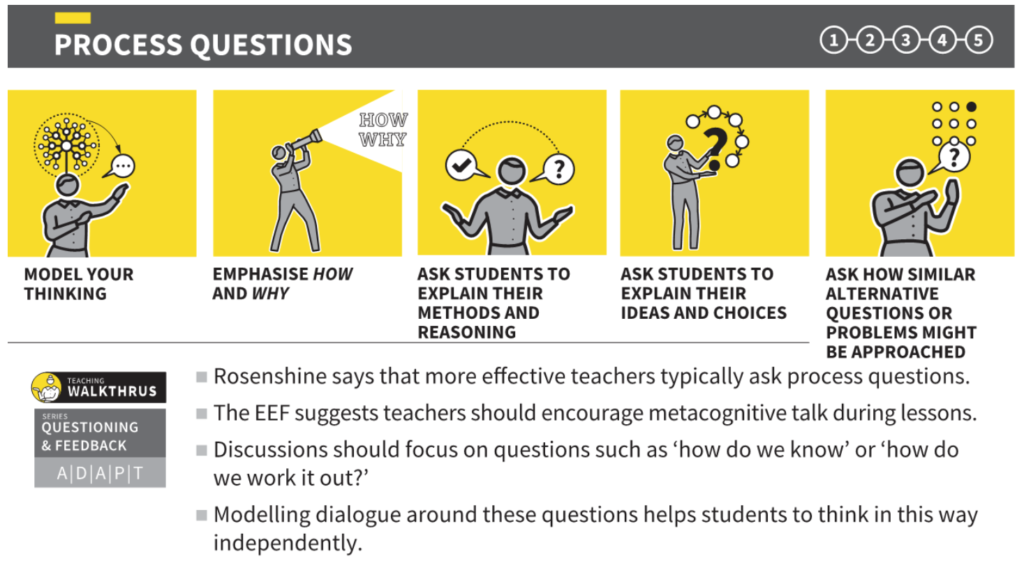

- Teachers are often too quick to move on with the lesson, and need, instead, to take more time surveying the class responses and following up with process questions (“How did you get 46 as the answer, James?”) which interrogate who has not learned what and what it is about their thought processes which leads them to making mistakes.

When aggregated, these micro-errors lead to corrupt feedback data from a seemingly simple, commonplace technique. Teachers are left none the wiser as to which students have learnt what.

So, what can you do to improve your (and your students’) use of mini-whiteboards? Well, I have been doing lots of work with Tom Sherrington recently and find the WalkThrus resources incredibly helpful. In the first WalkThrus series, there is a WalkThru for mini-whiteboards called “Show-me boards”:

What I like about the WalkThrus is how they are detailed but not completely prescriptive. Using the “Show-me board” WalkThru I would add the detail of, “Ensure the students hide/cover what they are writing from their neighbours” and, “When the students have written their answer, turn the board over on the desk, ready for my 3-2-1 instruction”. I would probably add, “Take time to survey the class before choosing which students to interrogate further using process questions”. The latter can be improved by using the “Process Question” WalkThru:

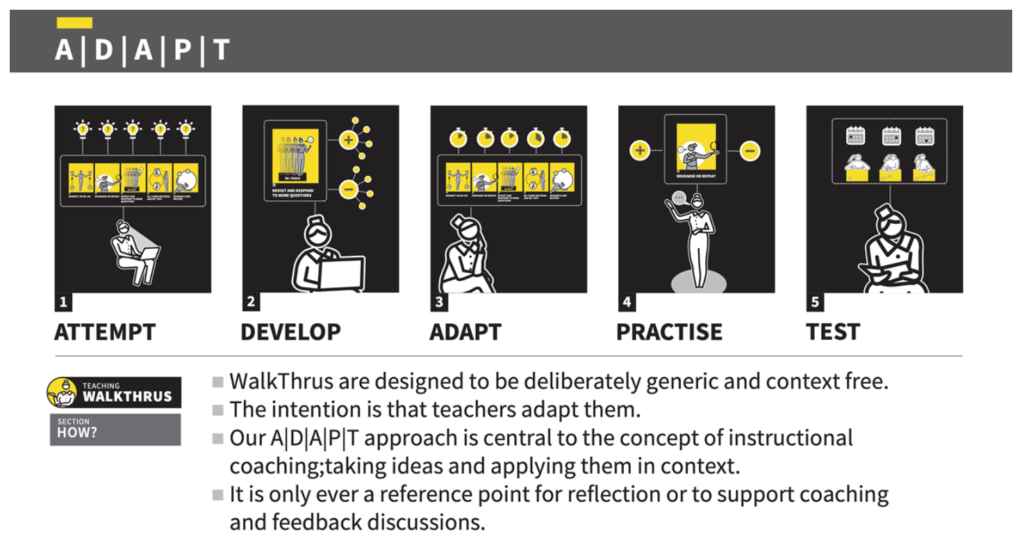

The WalkThrus series acknowledges that teachers will want to modify the individual 5-step WalkThrus for themselves, using the ADAPT process:

Improving your teaching can require diligence and attention to detail. There is no universal panacea to cure all teaching & learning ills. Instead, getting better in the classroom requires diligence and attention to detail, it requires teachers to be deliberate in their practice.

On a on a wet, windy Thursday afternoon in November try to be consciously competent when you’re teaching, even when using a technique which seems so ordinarily simple, like mini-whiteboards.