Dave Williams always makes me laugh. He is a very funny man. And I thought of him last weekend when I listened to Barbara Oakley’s keynote speech at researchED Dublin.

With utter clarity, Barbara explained how our brains learn. What she described was ostensibly familiar, but such was the lucidity of her entertaining and challenging talk, I now understand in much greater depth how our brains make memories out of what we are taught and how we recall those memories when we need them to solve challenges.

One thing that furthered my understanding was Barbara’s comments on current thinking about embedding memories. She asked the simple question, “If you are given the choice between two identical academic courses, one delivered with humour and one not, which would you prefer to experience?” The answer is, of course, obvious. And that is what reminded me of Dave Williams.

Dave Williams taught me A Level English Literature. Love’s Labour’s Lost, The Return of the Native, The Mill on the Floss, The General Prologue and The Wife of Bath’s Tale were Dave’s choice of texts for his half of the course. A quick glance at the copies of the texts (which are still on my bookshelves) shows that we must have read every word on every page. He never missed a significant connotation. And whilst I enjoyed his wit, under Dave’s tutelage I also revelled in being able to understand literary texts I would have found impenetrable. Dave’s funny and precise teaching made the densest texts accessible to the most diffident of students.

So, when Barbara went on to explain how the chemical dopamine is, perhaps, what binds together neurons and secures what we have learnt in our long-term memory, she made complete sense. Dopamine is released when we enjoy something and when we achieve something, especially when we have had to struggle to secure that achievement. Dave ‘Dopamine’ Williams was a truly great teacher.

And if you think about it, our best teaching is when we enjoy what we are teaching and when our students "get it". When I began teaching at Huntington School in 1998, I worked with Karl Elwell to introduce Media Studies A Level. We fed off each other’s enthusiasm. The more we enjoyed it, the harder we worked. Several students in our first class went on to study Media at university. One of them, Matt O’Brien, has his own film production company. I even had an article on teaching the gangster movie published in “In The Picture” magazine in 2002. Media Studies under Karl’s leadership is still thriving at Huntington, two decades on.

When Karl and I met one of the media students from our inaugural cohort a few years ago he said that they had worked hard because we were working so hard. They felt they couldn’t let us down.

Teaching what you love makes sense, doesn’t it? I was delighted when Hugh Richards, subject leader of History at Huntington, introduced a half-term long “Teach what you love” unit into every year group’s curriculum scheme, where his department colleagues could literally teach about an aspect of history which they loved for half a term, as long as they shared resources and explained to the rest of the department why they had chosen that topic.

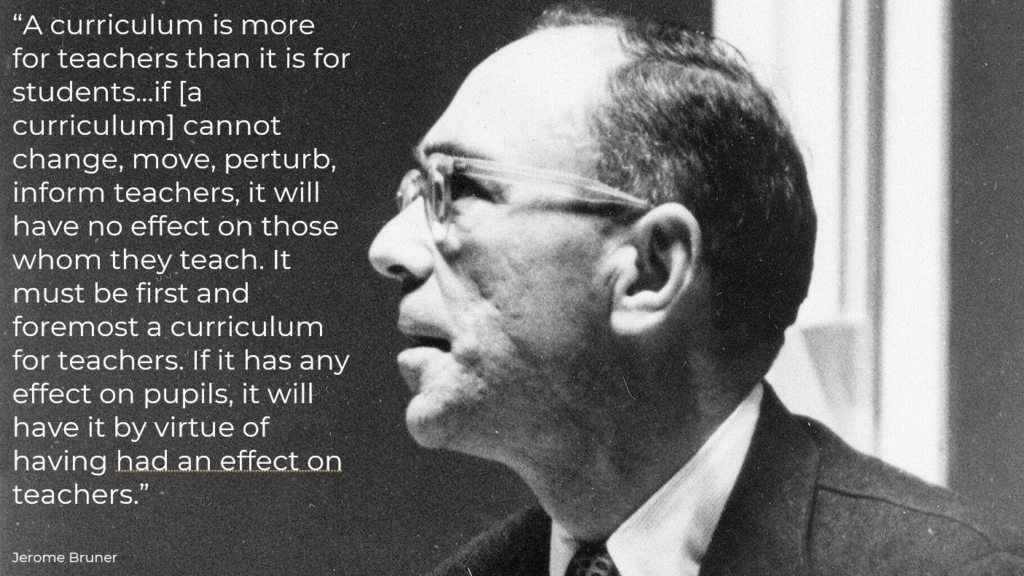

I recently re-read Jerome Bruner’s Process of Education (1960). In the 1977 reprint he makes a striking claim: “A curriculum is more for teachers than it is for students…if [a curriculum] cannot change, move, perturb, inform teachers, it will have no effect on those whom they teach. It must be first and foremost a curriculum for teachers. If it has any effect on pupils, it will have it by virtue of having had an effect on teachers.” Where you have the chance…Teach. What. You. Love!

Now both retired from English teaching, Dave and I are still in close contact. He has been a lifelong friend and he makes me laugh every time we speak. I know now that Love’s Labour’s Lost didn’t thrill him, but 40 years ago you wouldn’t have detected that for a second. As the peerless Chris Such says…