‘I’m writing immediately in case I don’t write at all – the usual thing is that I delude myself into thinking a moment will come when I can write the “real” letter.’

‘Even at 63, I’ve not learned that what’s put aside, stays aside.’

I’ve just finished reading The Letters of Seamus Heaney, a Christmas gift to myself.

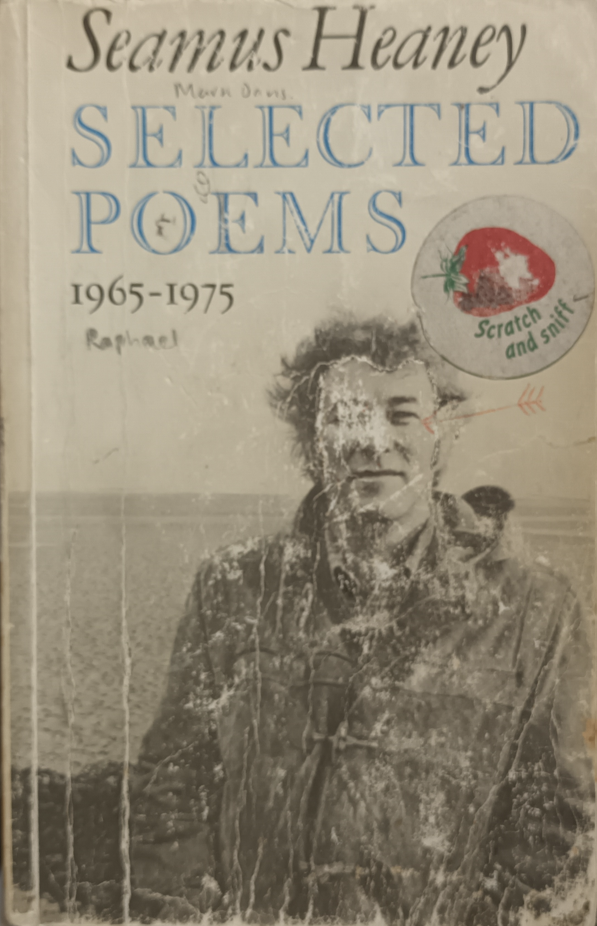

Ever since Marion Greene taught me Heaney’s Selected Poems, 1965-1975, the Irishman has been the one for me. Studying Heaney’s poetry was truly life changing. When I read his thoughts about finding a poetic voice, they seemed to me completely true:

‘Finding a voice means that you can get your own feeling into your own words and that your words have the feel of you about them…How, then, do you find it? In practice, you hear it coming from somebody else, you hear something in another writer’s sounds that flows in through your ear and enters the echo-chamber of your head and delights your whole nervous system in such a way that your reaction will be, “Ah, I wish I had said that, in that particular way.” This other writer, in fact, has spoken something essential to you, something you recognise instinctively as a true sounding of aspects of yourself and your experience. And your first steps as a writer will be to imitate, consciously or unconsciously, those sounds that flowed in, that in-fluence.’

The only poem I’ve managed about my dad of any worth has Heaney’s stylistic influence woven throughout; it won the 1988 Robin Lee Memorial Poetry Prize at the University of Sussex.

MEMORIAL

E.H. Tomsett, 1927-1985

I

The dark of an

Anglo-Saxon

slide show – scrambling

to complete a

Milton essay

in the lecture

hall’s dimmed corner.

Undercover

operations

exposed by the

porter’s message –

Urgent: ’phone home.

I didn’t know,

(but really knew)

what was afoot.

Father’s minor

operation –

just routine, but

mother’s voice broke

cancerous news.

II

The fast train slows

softly into

London’s King’s Cross,

echoing its

entry into

York. Between the

two the journey

was smooth – contin-

uation ’til

destination

assured. The last

few miles were the

worst – knowing the

end is near but

not knowing when.

Suddenly it’s

over, ended

before it began.

Terminated.

III

Energetic

Jack Russells find

solemnity

impossible.

This canine shows

death scant respect,

resists my self-

imposed sorrow,

pulls me away

from the marble

memorial,

out the graveyard

gate, barking and

panting, alive

with riotous

celebration.

Heaney’s poem ‘Follower’ explores his sometimes troubled relationship between his farming background and his academic life-path. One of my early poems acknowledged my debt to Heaney, how my poetic voice mimicked his and, on a deeper level, how my study of his poetry – and a university education – led me away from my familial roots.

BREACH OF COPYRIGHT

Muffled in

the background

a record

of his voice.

I’m breaching

copyright,

taping his

soft Irish

tones, making

a sounding

of my own.

And that’s what

I do now,

this moment

captured with

borrowed words.

I’m Heaney’s

follower,

trapped in his

broad shadow.

When I began my A Levels for the second time – first time around I studied chemistry, biology and mathematics but had been kicked out after a term – I chose mathematics (because I could ‘do’ mathematics), economics (because you didn’t need the ‘O’ Level) and, scratching around for a third subject, chose English Literature. Heaney’s poetry was a set text and his poems fuelled my decision to pursue English at university, and then to become an English teacher.

In my second year, I studied modern poetry with Hugh Haughton. One day, waiting for the class to arrive, I noticed on his desk some poems written in a distinctive hand, using a black ink pen. They were early drafts of Heaney’s Haw Lantern sonnets, sent to Hugh by the man himself. It was a moment of unbearable excitement! Years later I met Heaney at a reading to raise funds for an extension to the university’s library, instigated by Lawrence Rainey. Indeed, Heaney had a close relationship with the University of York. I last heard him speak there some two months before he died. He was upsettingly frail, the reason, I am sure, why he couldn’t endure a post-reading book signing. He still displayed plenty of sparkle, however, an example of which I preserved in the following ditty:

FAMOUS SEAMUS

University of York, 26 June 2013

Question from microphone number 2:

My little brother says your poems are just death and potatoes.

Are there two other words to describe your poetry you’d want us to take away tonight?

He paused for thought.

Sheer genius

was his retort.

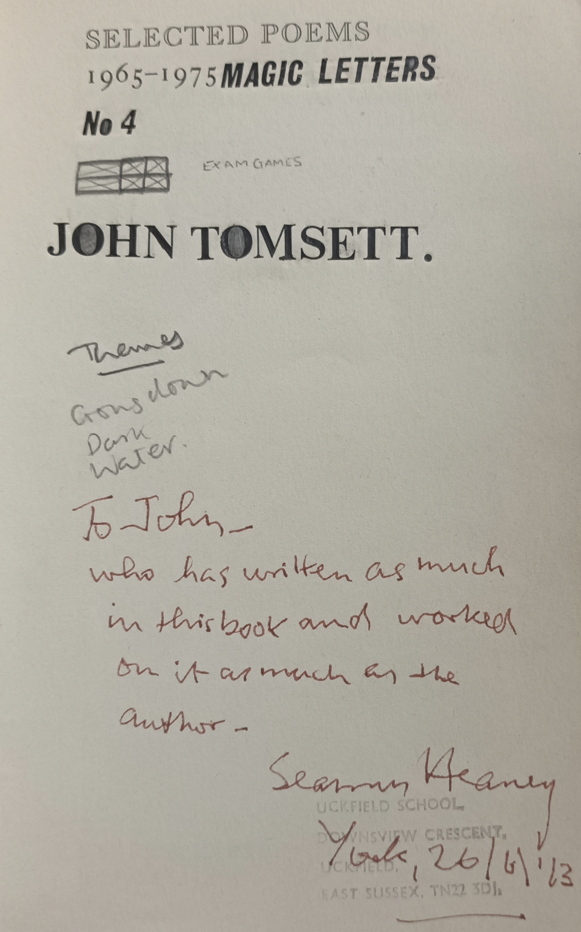

And, cheekily, Joan Concannon, the Festival Director, managed to sneak my copy of Seamus’ poems into the private dinner, and he signed it thus:

She said that he had looked at it a long time, especially at the cover, and mused on how young he appeared in the photograph.

The Letters of Seamus Heaney is a delight. I have been admonished already this Christmas for having my nose too deep inside its covers. So many things about him, revealed in these letters, resonate. Like me, he had a pacemaker fitted. He was reassuringly sweary. He found solace in the refrain of the Anglo-Saxon ‘Deor’ poem; as a green undergraduate the same poem helped me develop a philosophical acceptance of life’s vagaries, including my dad’s death… þæs ofereode, þisses swa mæg! ‘that passed away, so may this.’ He even quotes from Wallace Stevens’ poem ‘Sunday Morning’, the first poem Marion Greene ever taught us.

But what strikes me most about his letters is the sheer exhaustion he feels from the demands upon his time. Here is a man spread way too thinly, who cannot catch himself up: ‘I’ve been more or less on the run and have let time slip away.’ It’s as though Heaney is desperate for some time to himself, but is all too cognisant of his obligations to his friends – to whom he writes letters – and to his readers, with whom he corresponds. His mailbox is always brim full. He is forever overwhelmed by ‘the long-neglected, evaded and unwanted envelopes that I am too ready to keep evading and neglecting.’ He repeatedly begin letters with an apology for his tardiness in replying…

‘I’m sorry for the delay in replying to your letter…’

‘The only excuse I can offer for this tardy letter…’

‘As usual, I should have written long ago…’

‘I have to apologise to you for not writing…’

‘Forgive me for not writing earlier…’

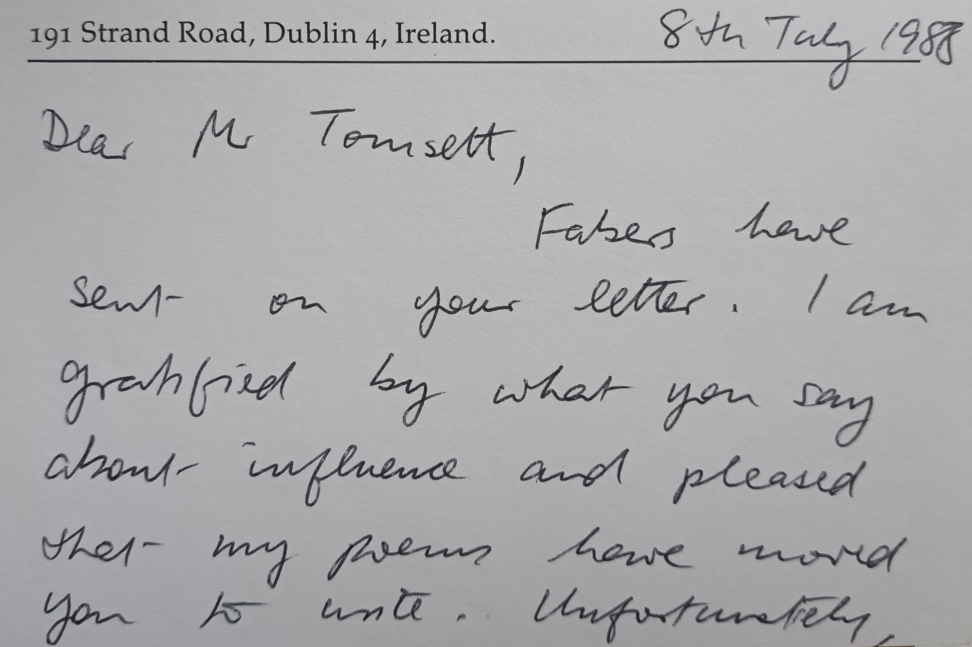

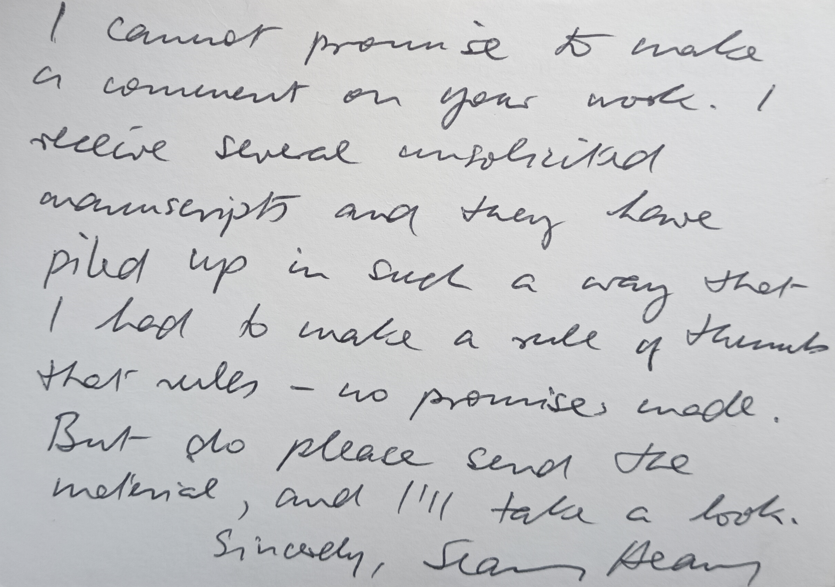

At one point he writes that he feels, ‘…like Gulliver, pinned down by single liens of obligation. No one of them is a big thing, each has singular meaning, but taken all in all, they panic me.’ All of which invokes in me a guilty twinge. As a green writer, I bothered Heaney with two letters. The first one included my poem ‘Breach of Copyright’. Incredibly, he took the time to reply:

Encouraged, I sent him three of my sonnets. In his response he said he had enjoyed this one the most – unsurprising, perhaps, considering his love of a good ink pen.

DIFFERENT STROKES

for Kate

His choice of pen remained the same,

From undergraduate Cambridge days

To signing his headmaster’s name –

A Waterman in mottled beige.

The cursive blacksmith’s art had honed

The ink-filled gold into a tool

For use by him and him alone –

His hand made them inseparable.

Gold outlasts all. The pen was left

A legacy, bequeathed to her

Whose writing pleased the family most:

But straining through the unknown curves

It snapped, to leave the nib’s new host

Mourning afresh, doubly bereft.

I once took that second note from Heaney into school to show some students and I’ve never seen it since. Every so often I search for it, fruitlessly. Now, having read his letters and knowing what an effort it was for him to tackle ‘the mail-midden’*, the very fact he wrote to me at all is consolation enough.

Indeed, the fact that I have one note from Seamus Heaney is a minor miracle.

*a ‘midden’ is a dung heap