“What should be taught to whom, and with what pedagogical object in mind? That master question is threefold: what, to whom, and how?”

Jerome Bruner

What gives teachers the authority to decide what our children should be taught? Why don’t we keep the roles of curriculum designer and teacher separate? When it comes to the school curriculum, why is teacher autonomy such a contested issue?

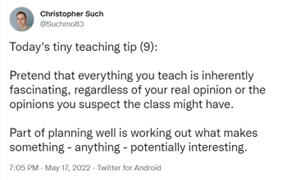

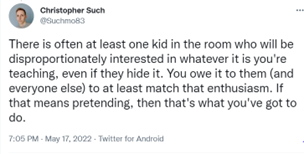

One possible answer to these questions lies in these two recent tweets by the ever-impressive Chris Such:

His sentiments allude unwittingly to the thinking of the educationalist Jerome Bruner, who, in his introduction to the 1977 edition of his book The Process of Education, wrote quite startlingly, “A curriculum is more for teachers than it is for students”. Bruner goes on to say that, “If [a curriculum] cannot change, move, perturb, inform teachers, it will have no effect on those whom they teach. It must be first and foremost a curriculum for teachers. If it has any effect on pupils, it will have it by virtue of having had an effect on teachers.” And, of course, this makes sense. If the person teaching you is not enthused about what they are teaching you, why should you be enthused? You may have taught the Romans a thousand times, but for the pupils in front of you it’s all new. As Chris Such says, pretend you’re enthusiastic even if you’re not. Teacher indifference is the enemy of pupil curiosity.

So, teachers are both curriculum constructors and teachers – arbiters of what should be taught and how it should be taught. As Dylan Wiliam points out, the National Curriculum is not a curriculum; rather, it is a list of the intended content pupils should learn and varies in its level of prescription from subject to subject. Within the National Curriculum there is a great deal of space for teachers to decide what to teach and how to teach it. If Bruner is right, it is in this space where teachers have the greatest opportunity to teach content that affects them and so affects the pupils.

Deciding what to teach, however, is complex. Christine Counsel’s core/hinterland metaphor is helpful, but controlling teachers as they go off-piste into irrelevancy bordering on the indulgent is a challenge. Dylan William’s principle of deciding upon the “Need to Know/Neat to Know” exerts, perhaps, a little more control over the individual teacher’s idiosyncrasies. Arnold’s “the best of what has been thought and said” is a decent enough guide, but it depends upon who is making such subjective judgements.

A school leadership team needs, then, to support its teachers by agreeing with them the principles and parameters for developing a curriculum. There will be tensions. And there will be difficult decisions to make. But a set of principles and parameters for teachers within which to develop the curriculum seems to me crucial. You might want to insist on including a certain local “colour” to your curriculum. In their first week at Fulford School in York, for instance, every single Year 7 enjoys a ride around the city in an open top tour bus, to make sure they have a sense of the historical jewels on their very doorsteps. Should that local “colour” be extra-curricular or embedded within units of work? Should it be core or hinterland? Need to know or neat to know? Who decides?

Is it right that two similar secondary schools within the same multi-academy trust have vastly differing Year 7 English curricula – one engaging in a full Shakespeare text whilst the other spends the same amount of curriculum time exploring conspiracy theories? Who is responsible for ensuring trust-wide standards? Does that matter? How far should personal curricular interests dictate what is taught in subjects where the National Curriculum is relatively prescription-free? What principles should a faith school agree? Or an Independent school? And what about schools that claim to deliver “a world class curriculum”. What does that mean? And as far as I am aware, no one has ever said they don’t have the highest expectations for their pupils…

Curriculum development, will, as Stenhouse claimed, be founded upon teacher development. None of us is a subject expert. We have approximately 600,000 teachers in this country, a mixed prior attainment group of practitioners. I have a degree in English Literature but ask me to teach Measure for Measure and I would need a couple of weeks to prepare. If teachers are to be responsible for both developing the curriculum and teaching what they develop in a way that children will learn what they are taught, they need the time and resources to fulfil both responsibilities. But first they need the school leadership to agree a set of principles and parameters for them to operate within when developing the curriculum; getting agreement, however, will be a challenge…

As Mary Myatt and I say, “Informed debate is the fuel of curriculum development”, and everything I have written here is a starting point, not the last word. If you would like to join us in discussing how to shape a rich, challenging, ambitious curriculum for all pupils, then have a think about signing up for our Huh Leaders Course, details of which can be found here.