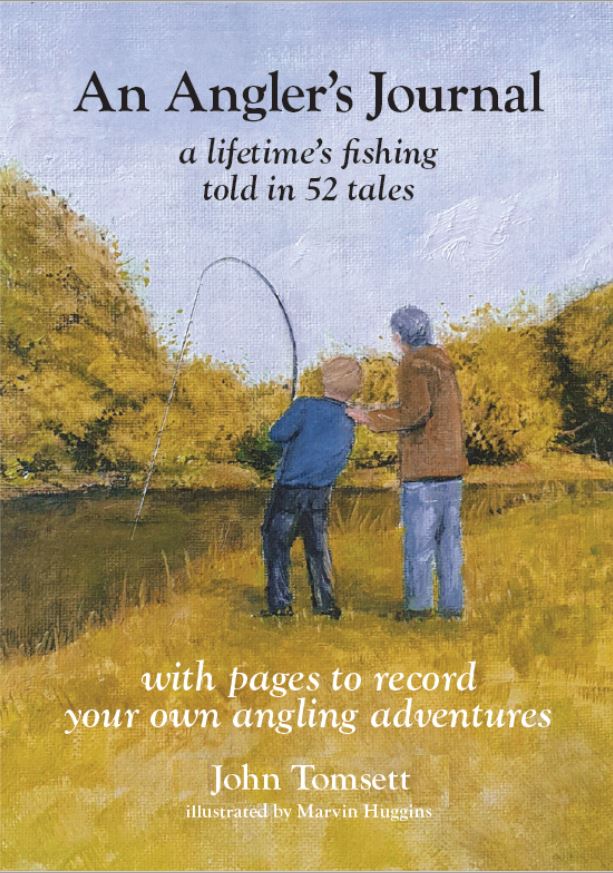

Last year I published An Angler's Journal, my first foray into writing about fishing. You can buy a copy on Amazon by clicking the image below. A few weeks ago The Economist magazine advertised for a writer for their "Britain" section. All you had to do was submit a CV and an unpublished article of 600 words. My article is published here; the fact I am publishing it confirms that my application was, predictably, unsuccessful!

Nowadays, Britons all want their own corner of the great outdoors. The most sought after feature of a new home? Post-pandemic, it’s a garden, of course. And who wants to live in the city any longer? Rather than abide in Manchester, try Didsbury. Say no to Central London, say yes to Dulwich.

With this new interest in country life has come an increased zest for rural pursuits. You may well think that Amazon, Zoom and cardboard manufacturers have been the big pandemic winners, but an unlikely beneficiary of Covid-19 has been the Environment Agency, the body responsible for fishing licence sales. It transpires that one of the activities which has been virtually exempt from lockdown restrictions in Britain has been angling. Dangling a worm on a hook in the local river makes the daily exercise routine just that bit more interesting. Since April 2020, over 100,000 Britons have taken up the sport and fishing licence sales have passed the one million mark.

But beyond being a legitimate pastime which will not arouse the interest of the local Covid-Warden, why on earth are so many people in the UK going fishing?

The answer lies, perhaps, in some fundamental realignment of priorities, one of which is spending patterns. People come to realise at different times in their lives that material things really do not matter and the pandemic has accelerated that process. Increasing numbers of the British public now know that a world built on capitalism – which depends upon people purchasing stuff they do not need – makes little sense.

People can survive quite nicely without going shopping. According to the Bank of England, the UK has an extra £160 billion in personal savings, an average of £5,500 per household. Many Britons now have money left over at the end of the month to spend on experiences, rather than material goods. Beyond this new-found affordability, the advantages of fishing are myriad: it is accessible to people of all ages; there are excellent facilities UK-wide, where stocked carp ensure a fish every cast; and fishing appeals to the primal instinct to hunt for food. A salmon caught in a river like the Yorkshire Esk – which hours earlier was swimming in the North Sea – tastes heavenly oven-cooked in foil with a knob of butter.

And then there is the sheer beauty of the British countryside, captured most vividly on camera in Mortimer & Whitehouse: Gone Fishing, the BBC’s unlikely gem. It follows two ageing comedians as they go fishing, eat good food and sleep in fabulous accommodation. Its success is rooted in how the pair’s idle chatter suddenly gives way to gentle wisdom. The show’s two protagonists rarely catch fish, but the sublime setting of each episode compensates for their empty nets. The show attracts nearly 2 million viewers.

So, given this sudden spike in the popularity of the sport, what will the Environment Agency do with its increased revenue? A substantial part of the proceeds from licence sales will go towards the Get Fishing Fund, a scheme designed to encourage more Britons to try angling for the first time or encourage ex-anglers back onto the riverbank. With the British government’s continued support of the hunting-fishing brigade, there seems little reason why the UK obsession with the piscine world should decline any time soon.

The pandemic has changed everything. The French once dubbed Britain a nation of shopkeepers, but the high street is a bleak place which has emptied quicker than you can say Debenhams. Move to the countryside, work from home and buy yourself a fishing licence. Les Britanniques are all anglers now.