Earlier this year I catalogued the many insights gleaned from educational experts which have been most influential in my curriculum thinking, in a post entitled, This much I know about… the principles of curriculum planning in action. In a series of short essays I am exemplifying in more detail ten of those influential insights, and explaining why I think they are so important to progressing pupils’ learning. This post explores the importance of Dylan Wiliam’s concept of the NEED to know and the NEAT to know when planning units of work.

“How do you respond to colleagues who say that there is too much content to cover in the curriculum?” asked Mary Myatt. We were interviewing Dylan Wiliam about his pamphlet Principled Curriculum Design which he published a decade ago.

Dylan replied with his usual common-sense wisdom: ‘You say to a subject leader, “Designate 20% of the content as desirable rather than essential.” That’s how you build in the slack. So, if you have a unit that’s going to last six weeks, what are the outcomes that are essential and what are the outcomes that are desirable, and at the end of week five the students might do a test, and if the students do well, you do the desirable in week 6, if they don’t do well you go back and do the essential in more detail in the spare final week. The phrase I like to use is NEED to know vs NEAT to know…it would be NEAT for my students to know this, but it’s not essential.’ He went on to say that subject leaders will claim the content is all essential. But, the elements of the content of a subject/unit of work have relative importance, and the work of the subject expert is to know what is NEED to know and what is NEAT to know, and to shape the curriculum according to the relative importance of each element of the content.

Dylan exemplified the NEED/NEAT to know by comparing particle theory and phases of the moon; students’ understanding of what is coming up in the science curriculum depends upon them understanding particle theory, whereas understanding the phases of the moon is not an essential building block for what follows in the weeks/months/years ahead. It may be possible to avoid teaching the phases of the moon completely, and not reduce students’ chances of succeeding in GCSE science (dons hard hat in anticipation of attack from science teachers everywhere!).

Of course, it is hard to stop doing stuff. I worked with a subject leader of History recently, and asked him to look at his unit on teaching the slave trade. He claimed every one of his ten lessons was NEED to know. When he took me through each of the ten lessons, lesson 5 was entitled, ‘A day in the life of a plantation worker’. I challenged whether that lesson was NEED to know. He said that one of the reasons why the abolitionists were successful was down to their ability to persuade their opponents to feel empathy for plantation workers, and that was why lesson 5 was in the scheme of work. We debated a bit longer and he finally conceded that in terms of what students NEED to know about the slave trade, ‘A day in the life of a plantation worker’ was NEAT to know. He then shifted that lesson to the very end of the unit, so that if he needed time to ensure every student had understood the NEED to know, he could dispense with that lesson and reteach the NEED to know content.

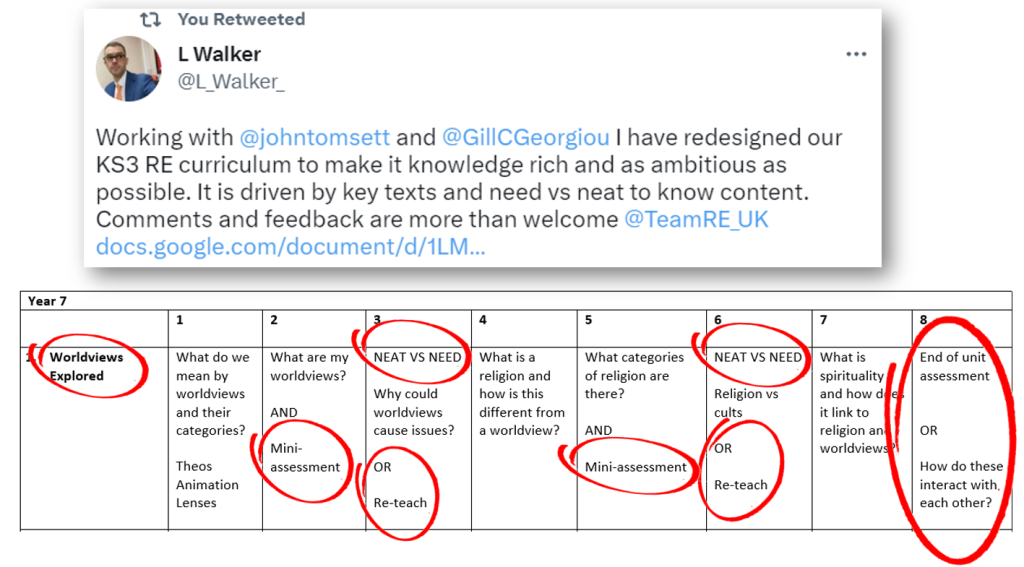

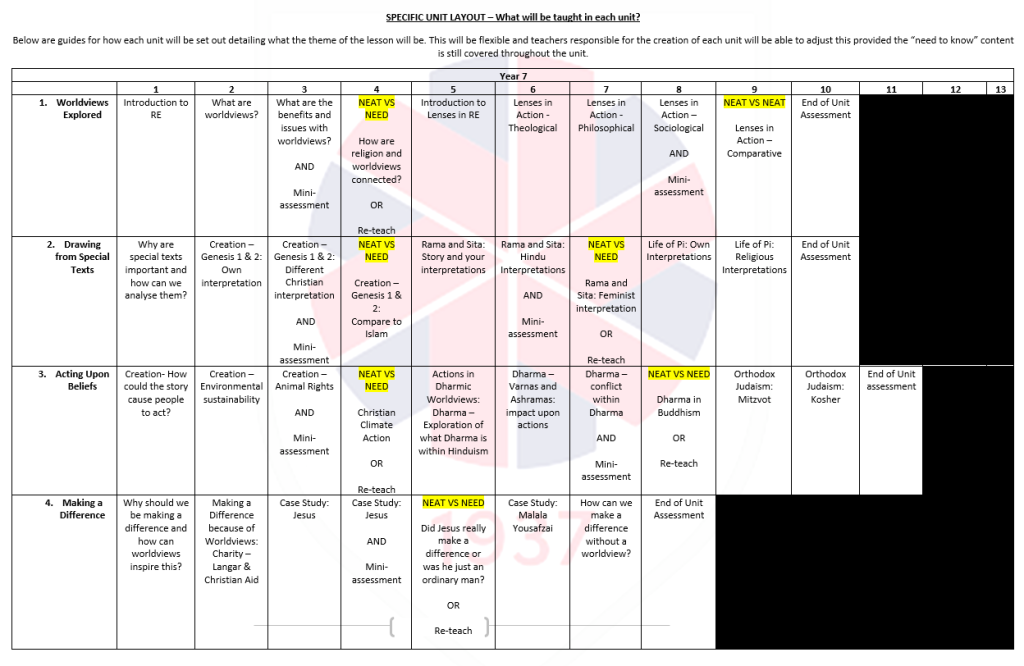

After I spent some time working with him on curriculum, the head of humanities at Toll Bar Academy in Grimsby, Liam Walker, has reshaped his schemes around the NEED/NEAT principle. Generously, he has made his material freely available here.

If you compare the image above with the image below, what I really like is how Liam’s first iteration of the “Worldviews Explained” unit has been modified over the past year. As Huh, the god of endlessness, creativity, fertility and regeneration might have said, developing the curriculum is a never-ending story…

So, when you are planning your schemes of work, debating the relative importance of a unit of work’s content in terms of what students NEED to know is, perhaps, only the starting point. How you then translate that into a plan for teaching that unit, so that you create yourself teaching time to adapt what you do in the light of what assessments are telling you about what students have learnt of what you’ve taught them, is the crucial, nuanced next step.

On 14 December, Mary Myatt, Tom Sherrington and I will be in London, talking about what we have learnt over the years about the curriculum. The event is called: Curriculum Masterclasses: A Christmas Celebration! It is only £30 (to cover costs) and John Catt Education have thrown in a free book of your choice from the range of books the three of us have published. You can book a ticket here. Come and join us!